Innovation – the attempt to try out new or improved products, processes or ways to do things – has always been with us. However, society’s attitude towards innovation has varied a lot throughout history. Today innovation appears as relevant as ever. Firms care about innovation because their future depends on it. Politicians care about innovation because of its (desirable) social and economic consequences, and “innovation policy” has emerged as an important field of politics. Scholars are interested in innovation too (and increasingly so). In a survey Bart Verspagen and I estimated that nowadays several thousand researchers study the phenomenon (Fagerberg and Verspagen 2009).

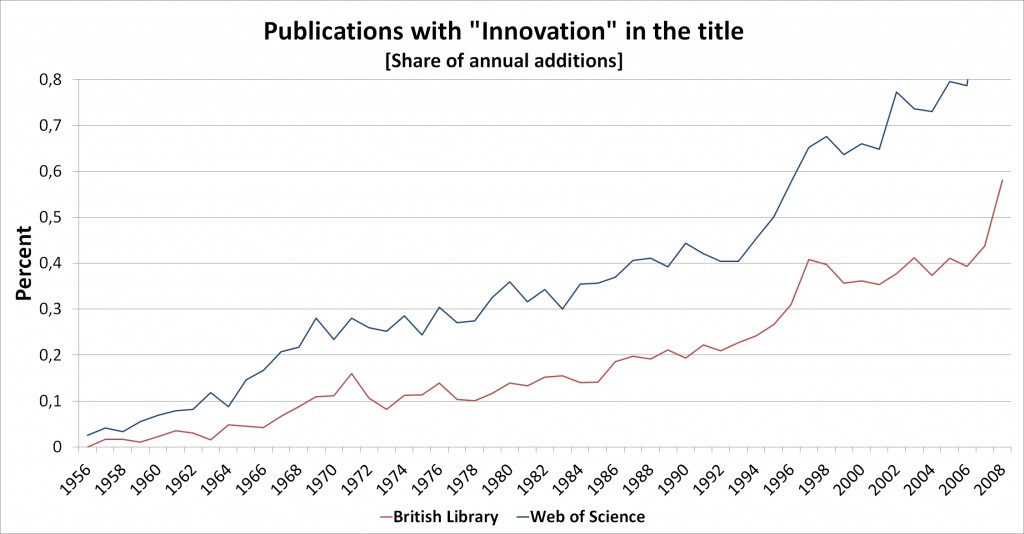

It has not always been like that. For a long time scholarly contributions about innovation were extremely rare. The major exception was the Austrian-American economist Josef Schumpeter, who already a century ago advanced a theory in which innovation, and the social agents underpinning it, was seen as the driving force of economic development (for more information see Fagerberg 2003). At the time he had few followers, however. In fact, as the Figure shows, as late as around 1960 the number of new publications focusing on innovation (at least as reflected in the title) was extremely low. This started to change in the 1960s, though, and from that time onwards scholarly interest in the phenomenon has increased steadily with – as the Figure shows – a particularly steep rise in recent years.

An important pioneer within innovation-studies was Christopher Freeman, the first director of SPRU (Science Policy Research Unit, the University of Sussex, established in 1966) and founding editor of the journal Research Policy. Freeman, who built on Schumpeter’s ideas, strongly emphasized the need for a broad perspective that included not only the emergence of new products, processes etc. but also their diffusion in the social and economic system. He was an ardent believer in multi-and inter-disciplinarity and from the very beginning SPRU had a multi-disciplinary research staff (see Fagerberg et al. 2011 for more on Freeman’s contribution to innovation-studies ). Freeman was also the person who attracted me to the emerging field. I became a doctoral student at SPRU and took a Ph.D. degree there in 1989. You can download my D.Phil. thesis – Technology, Growth and Trade: Schumpeterian Perspectives (1988) – from the university of Sussex, 7 chapters, 246 pages.

Innovation and the global economy

My research for the Ph.D. came to focus on the role that technology and innovation play for the international competitiveness and economic growth of countries. I was inspired by Schumpeter’s argument that economists tend to focus too much on price competition. Or as he puts it:

“But in capitalist reality as distinguished from its textbook picture, it is not that kind of competition that counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization (…) – competition which commands a decisive cost or quality advantage and which strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives. ” (Schumpeter 1943, p. 84)

I published a paper on technology and growth (“A Technology Gap Approach to Why Growth Rates Differ”) in Research Policy in 1987 and another on “International Competitiveness” in Economic Journal in 1988 . Both of these were based on Schumpeter’s idea of technological competition (or innovation) – rather than price competition – as the driving force behind economic development. While these papers focused on the country level, the perspective developed there might be just as relevant for analysing the performance of regions within countries, and later, together with Bart Verspagen and others, the analysis was extended to include regional dynamics as well. A selection of my papers in this area is published as a book (Technology, Growth and Competitiveness, Edward Elgar, 2002). You can download the list of content and introduction . The latter also tells the story of how I have come to look at global dynamics in the way I do.

Innovation and development

One popular perception of innovation that one meets in media every day is that it has to do with developing brand new, advanced solutions for sophisticated, well-off customers, through exploitation of the most recent advances in knowledge. Such innovation is normally seen as carried out by highly educated labour in R&D intensive companies, being large or small, with strong ties to leading centers of excellence in the scientific world. In this sense innovation is a typical “first world” activity. There is, however, another way to look at innovation that goes significantly beyond the high-tech picture just described. In this broader perspective, innovation – the attempt to try out new or improved products, processes or ways of doing things – is an aspect of most if not all economic activities. It includes not only technologically new products and processes but also improvements in areas such as logistics, distribution and marketing. Hence, even in so-called low-tech industries, there may be a lot of innovation going on. Moreover, the term innovation may also be used for changes that are new to the local context, even if the contribution to the global knowledge frontier is negligible. Thus, in this broader sense innovation may be as relevant in the developing part of the world as elsewhere.

Already in my first attempts to analyze “why growth rates differ” I wanted to include not only developed economies but also countries in the process of “catching up”. But the analysis was much constrained by lack of relevant data. Since then, however, there has been a growing effort to produce relevant statistics for a wider set of countries (including developing ones) and this implies that the possibility for analyzing these issues in more depth – and for a broader range of countries – has improved a lot. In two more recent articles, “The Competitiveness of Nations: Why Some Countries Prosper While Others Fall Behind?” in World Development 2007 (with Martin Srholec and Mark Knell) and ”National Innovation systems, capabilities and economic development” in Research Policy 2008 (with Martin Srholec), I tap into this potential. The analysis presented there clearly suggests that innovation, and the technological capabilities it depends on, are just as relevant for countries in the process of catching up as for the already developed part of the world. Successful capability building also depends on what politicians do and for a discussion of this issue, see Innovation and Catching-Up (with Manuel Godinho), in Fagerberg et al (2004) “The Oxford Handbook of Innovation” (Oxford University Press). For an overview of innovation activities in the developing part of the world, as well as a survey of the relevant literature, see Innovation and Economic Development (with Martin Srcholec and Bart Verspagen) in Hall and Rosenberg (2010): “Handbook of the Economics of Innovation”, North Holland.

Technological and Social Capabilities

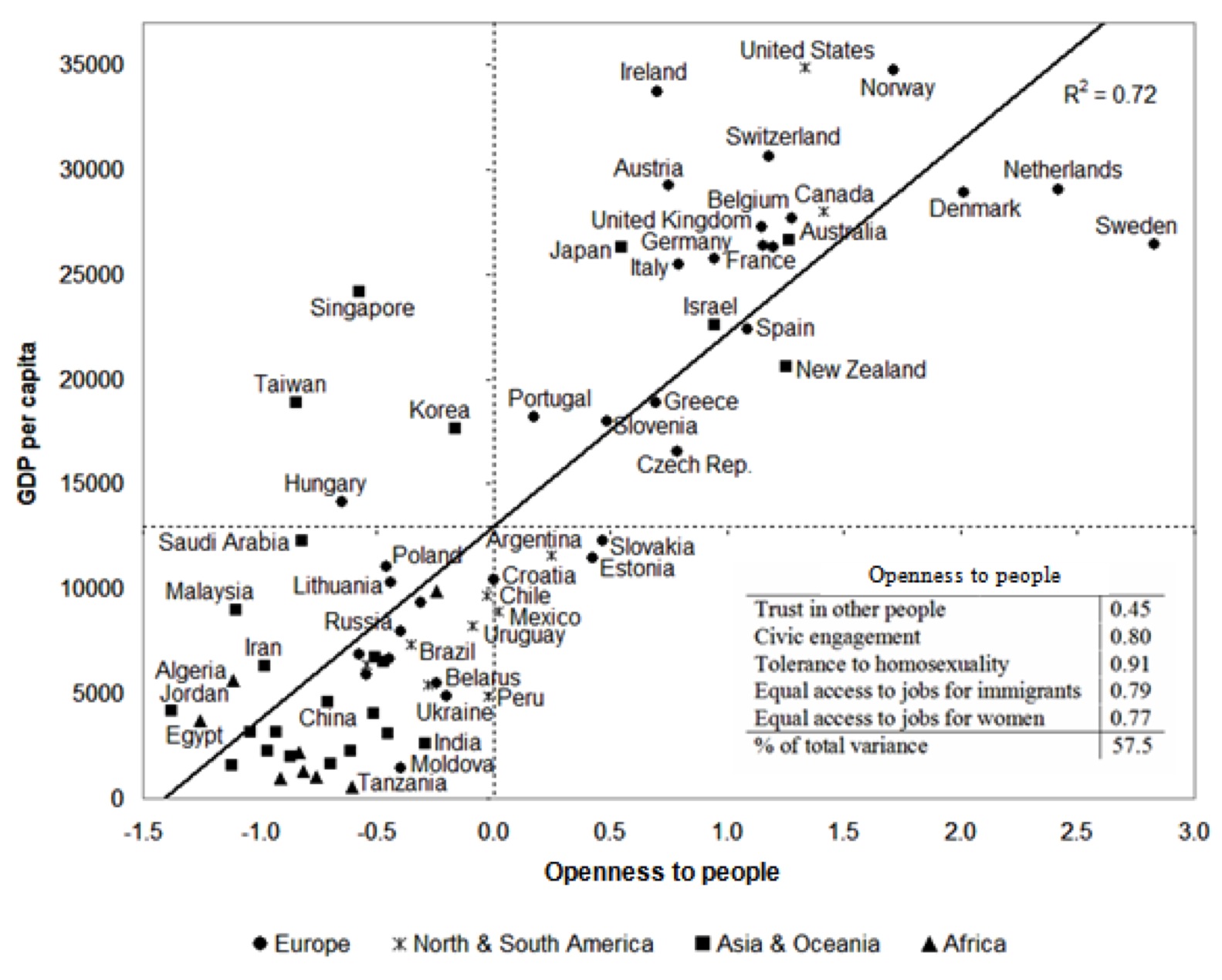

Innovation does not occur in a vacuum. Innovative firms, therefore, do not only depend on what happens inside the firm but also on the character of the broader environment in which they operate. The economic historian Moses Abramovitz, who I had the privilege to interact with during the early 1990s, used the notion “social capabilities” for societal factors that influence firms’ activities (Abramovitz 1986). In this concept he included a broad range of social phenomena, from the supply of skills via the quality of governance to norms and attitudes that support (or hamper) economic activities (another much used term for the latter is “social capital”). Such societal factors may be challenging to measure and include in empirical analysis, however, and Abramovitz himself was quite pessimistic in this regard. But in recent years several new sources of data have become available that in a better way reflect such factors, and together with Martin Srholec I have tried to exploit these opportunities in subsequent research (see, e.g, Fagerberg and Srholec 2008,Fagerberg 2010 and Fagerberg, Feldman and Srholec 2014). Although in several cases the nature of these data does not allow for very extensive testing of causality, the correlations are striking: Successful economic development clearly goes hand in hand with well-developed social capabilities. This holds not only for the more obvious aspects, education for instance, but also for the prevalence of norms and attitudes reflecting the openness of society to people with different characteristics (origin, gender and sexual orientation ), the degree of trust among its citizens and their willingness to participate in civic activities, what I call “openness to people”:

Arguably, countries that discriminate against an important part of their talent pool are shooting themselves in the foot. They may never catch up unless values, norms and associated practices change towards a more open, pluralistic stance. This is an important lesson. You may download the paper or see a video of the presentation.

Innovation systems, path dependency and policy

Between 2003 and 2008 I was responsible for the IPP (Innovation, Path-dependency and Policy) project, financed by the Norwegian Research Council, which focused on the characteristics of the Norwegian innovation system. While much previous work on national systems of innovation has been static in character and lacked historical depth, the IPP project applied a historical and evolutionary perspective. This led to a focus on the co-evolution of policy, the research infrastructure and key sectors in the economy. The project resulted in a book, published in 2009 by Oxford University Press, entitled ”Innovation, Path Dependency and Policy: The Norwegian case” (co-edited with David Mowery and Bart Verspagen). You will find a paper summarizing some of the main findings of the project here. The paper “Innovation Systems and Policy: A Tale of Three Countries” from 2016 extends the analyses to include two other Nordic countries as well.

Innovation policy and sustainability transitions

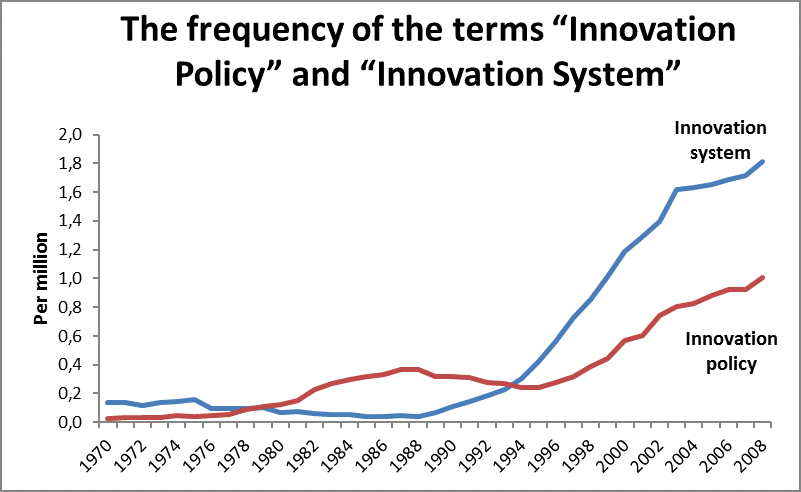

How far back in history interest for— and experimentation with— innovation policy can be traced, is an open question. Innovation is clearly not something new, and policy instruments that affect innovation, in one way or another, may have existed for a long time. However, the term innovation policy is of more recent origin. In fact, its use is – as the figure (based on Google Ngram Viewer) shows – closely related to the emergence and spread of the national systems of innovation approach from around 1990 onwards, emphasizing the central role of innovation in economic development as well as the broad range of factors influencing it.

Two papers (Fagerberg, 2017 and Edler & Fagerberg, 2017) trace the development of innovation policy as a separate field of politics, discuss the rationales for innovation policy and consider challenges related to governance and instrumentation. They particularly highlight the needs for a holistic analysis of factors influencing innovation; adequate analytical capabilities; and improvements in governance that contribute to better coordination and alignment of public policies influencing innovation across different parts (and levels) of government. The latter issue – innovation policy governance – is discussed in more detail in another recent paper, drawing on evidence from Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden (Fagerberg & Hutschenreiter, 2020)

Although the purpose of innovation policy often has been to invigorate the economic dynamics of a country, innovation policy can also have more specific aims, e.g., responding to challenges high up on policy makers’ agendas (so-called “mission-oriented” policies). This makes innovation policy very relevant in discussions of how to handle the climate challenge (or sustainability transitions more generally), the solutions of which arguably will require extensive changes in the economy, business-models and ways of life, i.e., innovation (see, e.g,. Fagerberg, Laestadius and Martin, 2016).

I discuss the role of innovation policy in sustainability transitions in a paper in Research Policy (Fagerberg, 2018). The paper starts by distilling some important insights on innovation from the accumulated research on this topic, and, with this in mind, discusses various policy approaches that have been suggested for influencing innovation and sustainability transitions. One of the conclusions is that policies supporting sustainability transitions, to be effective in their aims, cannot focus solely on supply-factors but need to engage with the demand side as well. I consider the role of demand-oriented innovation policy in sustainability transitions in more detail in another recent paper (Fagerberg 2022), highlighting three cases in which demand–oriented policy had a large impact, namely renewable energy in Denmark and Germany and electrical cars in Norway. Arguably, greatly helped by such policies, a global green shift – from fossil fuels to a system powered by renewables – is now well on its way (Fagerberg 2023a). Embracing this shift, and adapting it to the specific national (or regional) circumstances, may be the best opportunity policy-makers have in the pursuit of net zero emissions (Fagerberg 2023b).

Understanding innovation

Innovation is a multifaceted phenomenon that calls for insights from different disciplines and approaches. An important step in improving our understanding of innovation, therefore, is to bring together researchers with different backgrounds, try to develop a common knowledge base and work towards a shared understanding of the phenomenon. My motivation for initiating the TEARI project, which got support from the European Commission, was to contribute to this process. This I considered to be very important for the future of the field (and I still do). The project, the purpose of which was to produce a comprehensive overview and synthesis of the role played by innovation in modern societies, resulted in 2004 in the publication of a multi-disciplinary, multi-authored volume, “The Oxford Handbook of Innovation”, coedited with David Mowery and Richard Nelson. You may download the introduction to the handbook here.

Innovation studies

The handbook is an attempt to survey the “state of the art” of innovation studies. However, in my view it is also interesting to understand how the field has evolved towards its current stance, learn more about the characteristics of those active in this area and, not the least, explore the relationships between innovation studies and other disciplines (or inter-disciplinary fields). This may be of interest not only for researchers in this area (who may benefit from it in discussions of the field’s future for example) but also for scholars in neighbouring disciplines (or fields) and for those interested in how social science – and the world of science more generally – renews itself (for whom innovation studies may be an interesting case). Hence, I have, using different methods/approaches, devoted a good deal of energy to these issues. The paper “Christopher Freeman: Social science entrepreneur” (Research Policy 2011), for example, is mainly historical in its approach (supplemented by bibliometric information). In contrast, the evidence analyzed in“Innovation studies -The emerging structure of a new scientific field” (Research Policy 2009) comes from a web-based survey of around one thousand scholars in this area. The paper “Mobilizing for change: a study of research units in emerging scientific fields” (Research Policy 2012) is also based on a survey (albeit a different one) but this time supplemented by a number of case studies. Finally, “Innovation: Exploring the knowledge base”(Research Policy 2012) looks at the evolution of the knowledge base on innovation as evidenced by citations in eleven different handbooks on (various aspects of) innovation (published from the early 1990s onward).

References

- Abramovitz, M. 1986. Catching Up, Forging Ahead, and Falling Behind. Journal of Economic History, 46: 386-406.

- Clausen, T., J. Fagerberg and M. Gulbrandsen 2012. Mobilizing for change: a study of research units in emerging scientific fields. Research Policy 41(7), 1249- 1261.

- Edler, J Fagerberg. 2017. Innovation Policy: What, Why & How, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (1), 2-23.

- Fagerberg, J. 1987. A Technology Gap Approach to Why Growth Rates Differ, Research Policy 16: 87-99

- Fagerberg. J. 1988. International Competitiveness, The Economic Journal, 98 (June): 355-374.

- Fagerberg, J. 2002. Technology, Growth and Competitiveness: Selected Essays, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

- Fagerberg, J. 2003. Schumpeter and the revival of evolutionary economics: an appraisal of the literature, Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 13, 125-159

- Fagerberg, J. 2010. The changing global economic landscape: the factors that matter, In Robert M Solow & Jean-Philippe Touffut (ed.), The Shape of the Division of Labour: Nations, Industries and Households. Edward Elgar, p. 6 – 31.

- Fagerberg, J., 2017. Innovation Policy: Rationales, Lessons and Challenges, Journal of Economic Surveys , DOI: 10.1111/joes.12164.

- Fagerberg, J. 2018. Mobilizing innovation for sustainability transitions: A comment on transformative innovation policy. Research Policy 47(9): 1568-1576

- Fagerberg, J. 2022. Mobilizing innovation for the global green shift: The case for demand-oriented innovation policy, in Castellani,D., A. Perri, V. Scalera and A. Zanfei (2022) “Cross-border Innovation in a Changing World – Players, Places and Policies”, Oxford University Press, pp. 272-291

- Fagerberg, J. 2023a. “The global green shift: Where it comes from, how it works, and where it’s heading,” Working Papers on Innovation Studies 20230923, Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo.

- Fagerberg, J. 2023b. “Mobilizing innovation policy in the pursuit of net zero emissions: An evolutionary perspective,” Working Papers on Innovation Studies 20230108, Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo.

- Fagerberg, J., S. Laestadius & B. R. Martin, 2016. The Triple Challenge for Europe: The Economy, Climate Change, and Governance, Challenge, Volume 59, Issue 3, 2016, p. 178-204,

- Fagerberg, J., Fosaas, M., Bell, M., Martin, B.R. 2011. Christopher Freeman: Social science entrepreneur. Research Policy 40, 897-916

- Fagerberg, J., Fosaas, M. and Sapprasert, K. 2012. Innovation: Exploring the knowledge base, Research Policy 41, 1132-1153.

- Fagerberg, J., Godhino, M. 2004. Innovation and Catching-Up, in Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D., and Nelson, R. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2004, p. 514-544

- Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D., and Nelson, R (eds.) 2004. The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. and Verspagen, B. (eds.) 2009. Innovation, Path Dependency and Policy: The Norwegian case, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D. and Verspagen, B. 2009. The evolution of Norway’s national innovation system, Science and Public Policy, 36: 431-444.

- Fagerberg, J. and Srholec, M. 2008. National Innovation systems, capabilities and economic development, Research Policy, 37: 1417-1435

- Fagerberg, J, and Srholec, M. 2013. Knowledge, Capabilities and the Poverty Trap: The complex interplay between technological, social and geographical factors, in Meusburger,P., Glückler,J. and el Meskioui, M.(eds.): Knowledge and the Economy, Springer 2013, p. 113-137.

- Fagerberg, J., Srholec, M. and Knell, M. 2007. The Competitiveness of Nations: Why Some Countries Prosper While Others Fall Behind?, World Development, 35: 1595-1620.

- Fagerberg, J., Srholec, M., & Verspagen, B. 2010. Innovation and Economic Development. In B., Hall, & N., Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Innovation. Vol. II. North Holland, p. 833-872.

- Fagerberg, J. and Verspagen, B. 2009. Innovation studies -The emerging structure of a new scientific field, Research Policy, 38: 218-233

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1942) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, New York: Harper.